Singular Value Decomposition - Eigenvectors of A Symmetric Matrix

matrix

In this fourth post of the series, let’s first review the two concepts introduced in the last post — transpose and dot product — but in a new context.

Partitioned matrix ¶

When calculating the transpose of a matrix, it is usually useful to represent it as a partitioned matrix. For example, the matrix

can be also written as:

where

We can think of each column of

Therefore,

Each row of

Let matrix

where each column vector

For each element, the first subscript refers to the row number

and the second subscript to the column number.

Therefore,

Note that by convention, a vector is written as a column vector.

To write a row vector,

we write it as the transpose of a column vector.

The product of the

To calculate the dot product of two vectors R,

we can use a %*% b, as matrix multiplication.

Length of a Vector ¶

Now that we are familiar with the transpose and dot product,

we can define the length (also called the 2-norm) of vector

To normalize a vector

The normalized vector

which is the same as the output of eigen(mat_b).

As shown before, if we multiply (or divide) an eigenvector by a constant,

the new vector is still an eigenvector for the same eigenvalue.

Therefore, by normalizing an eigenvector corresponding to an eigenvalue,

we’d still have an eigenvector for that eigenvalue.

Revisit Eigenvectors ¶

Why are eigenvectors important to us?

As mentioned before, an eigenvector simplifies the matrix multiplication

into a scalar multiplication.

In addition, they have some more interesting properties.

Let me go back to matrix

In the previous post,

this matrix transformed a set of vectors eigen() to calculate its eigenvectors.

mat_a <- matrix(c(3, 0, 2, 2), 2)

eigen_a <- eigen(mat_a)

eigen_a

eigen() decomposition

$values

[1] 3 2

$vectors

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 1 -0.8944272

[2,] 0 0.4472136

We got two eigenvectors:

and the corresponding eigenvalues are:

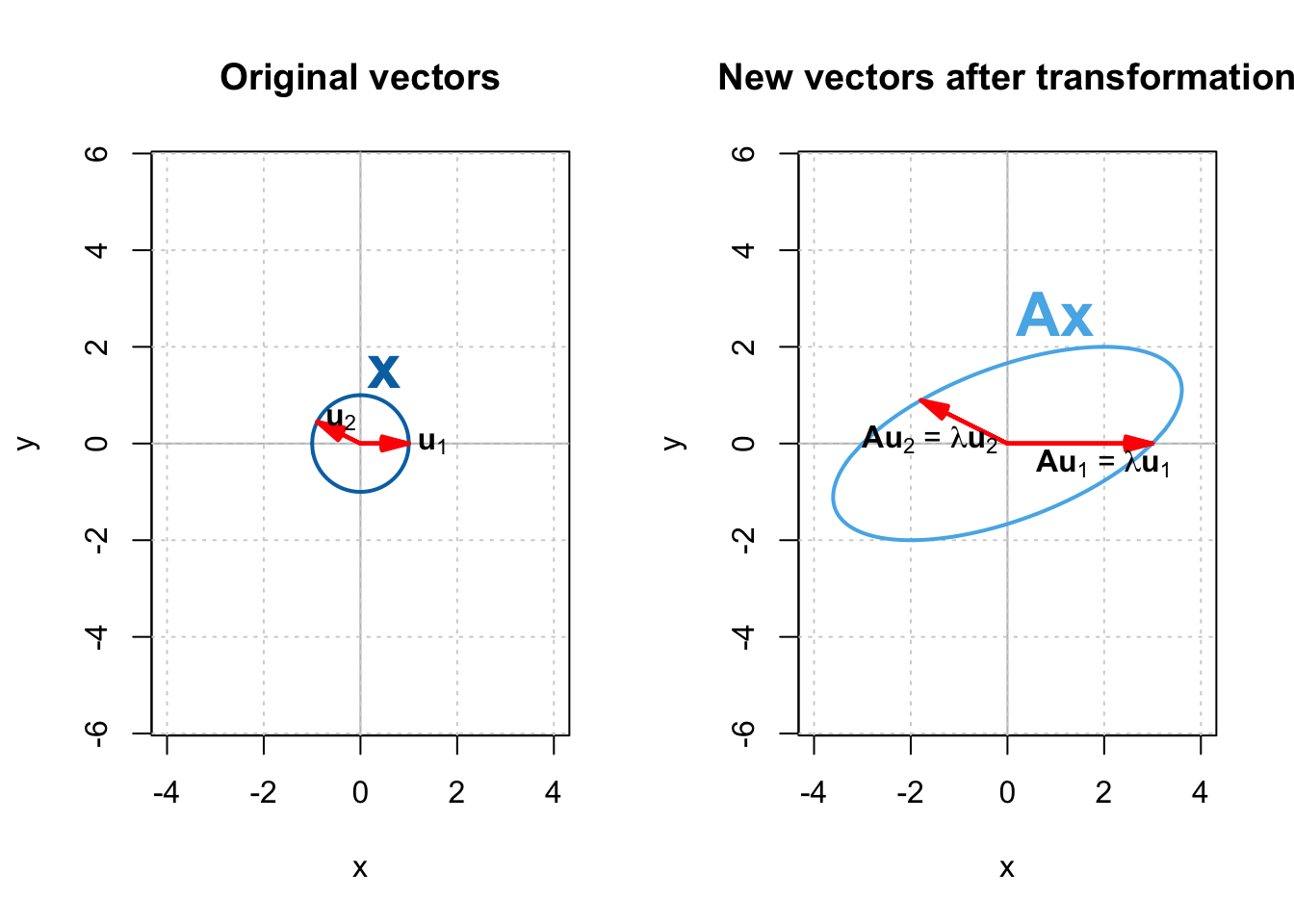

Now we plot

Every vector in

Let’s try another matrix:

It’s two eigenvectors:

and the corresponding eigenvalues are:

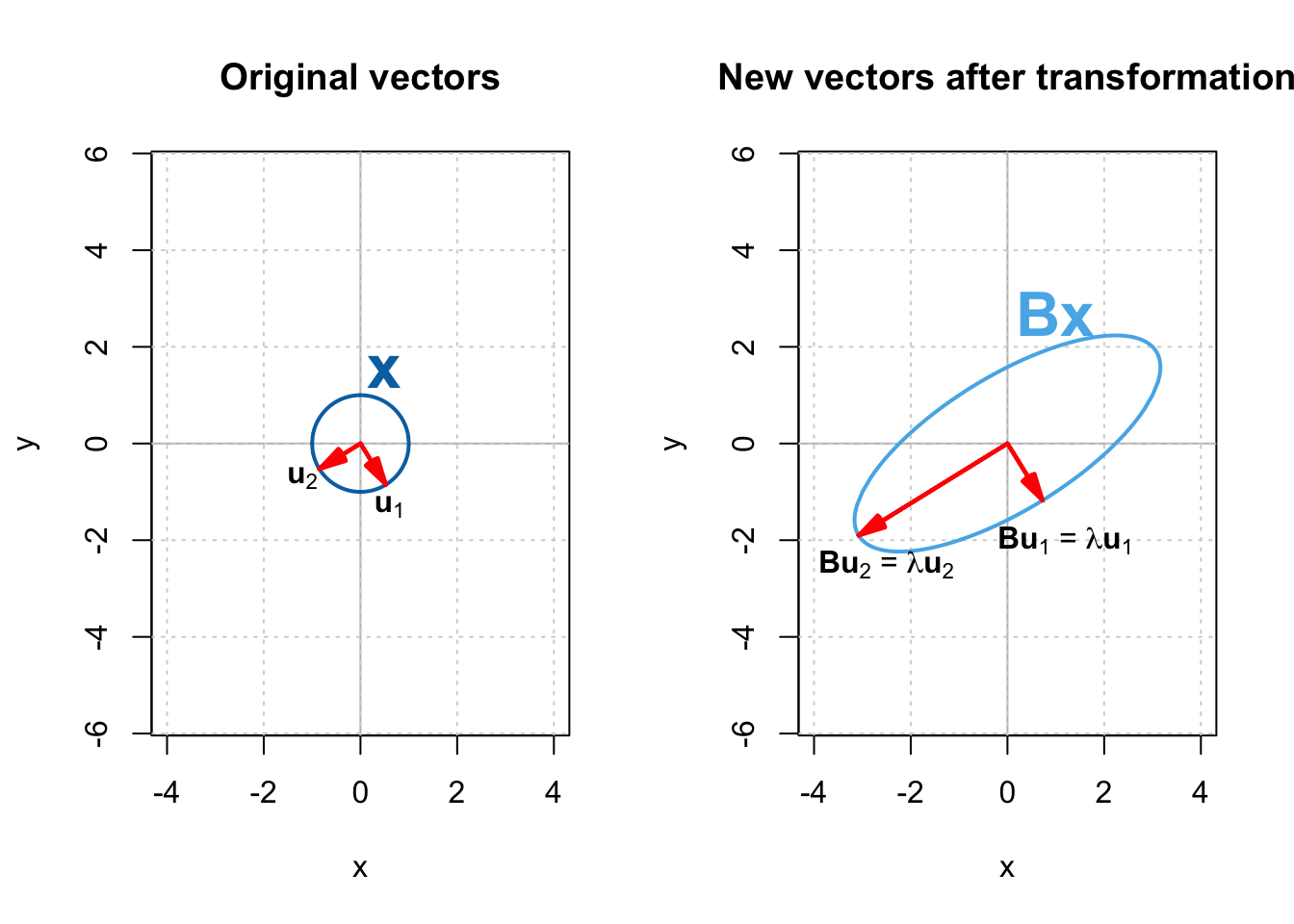

Figure 2 shows

This time, the eigenvectors have an interesting property.

They are along the major and minor axes of the ellipse (principal axes),

and are perpendicular to each other.

An ellipse can be thought of as a circle stretched or shrunk along its principal axes

as shown in Figure 2,

and matrix

How come the eigenvectors of

Elements on the main diagonal of a symmetric matrix are arbitrary,

but for the other elements, each element on row

Given that the initial vectors in

Therefore, the amount of stretching or shrinking along each eigenvector is proportional to the corresponding eigenvalue as shown in Figure 2.

When you have more stretching in the direction of an eigenvector, the eigenvalue corresponding to that eigenvector will be greater. In fact, if the absolute value of an eigenvector is greater than 1, the circle 𝕏 stretches along it; vice versa.

Let’s try another matrix:

The eigenvectors and corresponding eigenvalues are:

Now if we plot the transformed vectors, we get:

Now we have stretched

In the next post, we will continue discussing eigenvectors, but in the context of a basis for a vector space.